Hi, I'm Tyler Michael. Welcome to my review page, where I review Movies and TV shows from the past and present. I'm a big fan of films and I would love to share my love for them with you. I'll be posting new reviews almost every week. If you have any requests for a Movie or TV Show you'd like me to review, get in touch and I'll get to the review when I get a chance.

Search This Blog

Sunday, April 21, 2024

007 Game Rankings: Number 13. "Tomorrow Never Dies" (Ps1)

Saturday, April 6, 2024

007 Game Rankings: Number 14. "007 Racing" (Ps1)

Tuesday, April 2, 2024

Ranking 007 Video Games: Introduction

- I am Not a Gaming Critic: After explaining how lightly I look at video games, expect these reviews to not be based on the mindset of an expert on games but more from the perspective of a casual gamer who is judging the games on playability and capturing the spirit of the franchise.

- Expect Me to Talk About my Relationship with Some of the Games: If I sounded vague about how much the games mean to me, I will indeed discuss my nostalgia with them, since part of the reason for this list is to express my relationship with the games that helped me become a Bond fan.

- I'm Only Talking About Bond Games for Certain Systems: As much as I would love to play every single Bond game, I am only sticking with the games for the PlayStation, GameCube, and Nintendo 64. This means I will not be including Bond games for systems such as the Gameboy, Atari, or PC. Not only do I not have the resources to play the games, but looking at them, with the exception of NightFire for the PC, there's hardly anything for me to talk about because of how dull and lacking theatricality they are.

- I Will Not be Reviewing Online Multiplayer: While I plan to review most of the multiplayer modes in the games, I will not be reviewing online multiplayer. Barely anybody plays the online campaign (One of the reasons I'm not a fan of multiplayer games made for strictly online only), and I do not have the resources to take part in online mode at the current time.

- Bonus Section: As a special treat, at the end of each review, I will have a bonus section talking about my favorite and least favorite mission.

Monday, March 18, 2024

What is Film Noir?

James Naremore claims that it "has always been easier to recognize a film noir than to define the term." Naremore further states, "There is, in fact, no completely satisfactory way to organize the category; despite scores of books and essays that have been written about it, nobody is sure whether the films in question constitute a period, a genre, a cycle, a style, or simply a phenomenon." People's typical perception of film noir contains the following. The main characters are either anti-heroes wronged by the law or are working outside the law. To narrow down the main characters further, they would usually qualify as a hard-boiled, fedora -and trench coat-wearing detectives or wrongfully convicted men who wander into trouble at the wrong place, at the wrong time. The female characters are femme fatales, women who are cold, seductive, and selfish. In short, they are beautifully shallow monsters. The antagonists in film noirs are either corrupt officials or murderous criminals with little to no charm. Film noirs were ideally shot in black and white with heavy low-key lighting to create an ominous shadowy atmosphere, usually on empty foggy city streets, and in shabby apartments, smoky bars and diners. The question is, is it true that there are films that are considered noir that challenge people's ideas of the style?

Looking into the more obscure side of the style, two films that fit the category yet challenge the general perception of it are The Great Flamarion (1945) and Fear in the Night (1947). The best way to start when analyzing the two films is the beginning. It is not uncommon for a film noir to tell a chronologic story, yet it is seen as a staple of the style for the film to present itself through flashbacks. Typically, what leads to this narrative is an opening designed to get audiences immediately hooked with an action, leaving them with questions of how the protagonist made it to where he is now. The Great Flamarion uses this traditional approach. The film opens in Mexico inside a theatre as the camera slowly approaches the stage, catching an end of a performance and the beginning of another. The camera halts at a medium shot of a clown performing, only to have the performance interrupted by a gunshot heard off-screen. During the chaos, glimpses of the suspected crook are revealed as he climbs the ladder in an overhead shot. His face appears as he is walking on the scaffold above the stage, looking wounded as he hides from the authorities. Shortly after the chaos, we discover a woman was murdered, and her husband is falsely arrested for the crime. While finding out this info, part of it is seen through the P.O.V. of the man hiding up in the scaffolding viewing the conversation from above. With everybody gone, except for the clown, the man hiding falls onto the stage, where he is then comforted by the actor. The clown recognizes him as the film's title character, The Great Flamarion. Flamarion reveals he was the one who murdered the actress and that she shot him in self-defense. With no hope for survival from his wounds, Flamarion confesses the reason for the murder before dying, leading to a flashback officially beginning the film's story. With film noirs, a murder usually happens on the dark city streets. While the murder does take place inside the theater, the painted backdrop behind him resembles a city street.

Despite the unconventional setting, everything in The Great Flamarion's opening scene plays out as a typical film-noir. Fear in the Night's opening is utterly different. The film itself does not look like a film noir, more so a low-budget combination of a Hitchcockian thriller with cheesy spooky visuals that William Castle would be proud to exhibit in his gimmicky horror films. The background for the opening credits has blurry kaleidoscope imagery as loud dramatic music plays with a title as dramatic as if we were watching a teaser trailer for a low-budget old horror film or the midnight spook shows (before they were even a thing). The first image that does appear looks just as spooky and hokey, with a woman's head floating toward the screen over melancholy narration that sounds strangely distant. What follows is a murder scene played out as intense with the same surreal kaleidoscope-like imagery as the title sequence, this time adding blurry ripples, mirrors, dramatic close-up shots, heavy low-key lighting, and an overhead shot of the character spinning into a vortex. Vivian Sobchack mentions "that back projection is to film-noir space what flashbacks are to film-noir time. Not merely a tacky effect of a low-budget production, back projection is an aesthetic element that well serves noir's philosophical worldview, transforming it not only into something literal and materially realized but also producing a subtle yet significant effect on the viewer's sensual comprehension of cinematic meaning." The same can be said about the low budget aesthetics of the sequence. It looks fake yet creates an image straight out of a nightmare. While the sequence looks other worldly, the inner monologuing and the imagery of a man murdering a woman ground this surreal sequence making it appear we are gazing into someone's haunting memory.

The scene dissolves into an image of the protagonist Vince Grayson (played by a young DeForest Kelley) waking up in bed, believing it was all a dream hence the unusual imagery. Surprisingly, the character wakes up to find two thumbprints on his neck, a key, and a button from the nightmare. As in The Great Flamarion, there is a hook involving murder and a mystery that escalated quickly. Still, there are no flashbacks in the narrative, nor are the actual events supposedly happening. At least, that is not what the film wants audiences to think at first. The film is almost like an episode from The Twilight Zone, with a mystery that appears set in a supernatural realm. We, the audience, are wondering like the protagonist if what he envisioned was a dream or not. And if not, then how and why? It is not until the climax that it is made clear that everything that was shown in the film's opening did indeed happen. What audiences are witnessing is a flashback only shown from the delusions Vince was under, further creating a literal nightmare that is subtle with the meaning of what the viewer is seeing. In short, the film opens with a flashback without stating that it is one until the end.

A popular trope in film noir that the two films do not have is a protagonist who is a tough detective working outside the law. What the two films do share, however, is a doomed protagonist. Fear in the Night, despite its horror-thriller-like concept, does involve a character in trouble with the law all throughout. However, Vince does not have trouble with the law directly. He did not cause an accidental death that he knows he is responsible for, like Al Roberts in Detour. Vince is unsure if what he dreamed was real or not, based on the places, people, and things he sees relating to the dream he has never encountered until that moment. And he does not keep his suspected crime a secret from the authorities either. On the contrary, he has a brother-in-law in the police force to whom he confesses his crimes, who of course, shrugs it off as nothing more than a nightmare. It is not often that a protagonist in film noir confesses to a crime they did not commit.

Flamarion, character-wise, is the opposite of Vince. While Vince functions as the everyday social individual with a steady job, Flamarion is a successful antisocial showman with no likable qualities due to his arrogant and cold personality. The only thing he is devoted to is his work as a vaudeville marksman, spending many lonely hours in the dark perfecting his craft. He is so unlikable that without his mournful introduction any audience member could take him as a villain for his menacing appearance, brutish attitude, and a profession that can easily get him a job as a hitman. In fact, he does become a hitman at one point in the film by killing one of his stage actors during his act to make it seem like an accident. Usually, a protagonist committing murder would feel the guilt of some sort after or paranoia about the law finding out. But he does not show any of the two. He legally gets away with murder by convincing people it was an accident, and he thinks nothing of killing a man, not because he intended to be a cold-blooded murderer, it is because he was corrupted by something more dangerous than a gangster or thug: a femme fatale.

The woman corrupting Flamarion is his beautiful assistant, Connie (Mary Beth Hughes), who works with her alcoholic husband, Al (Dan Duryea), during the act. Connie is a maneater- a woman who never settles down with one man. She will marry a man or date him for a while until she gets bored and goes for the next man, she finds attractive. Just abandoning a man for another is not always easy for her, especially in the bonds of holy matrimony; that's where Flamarion comes to play in her little plan. She has no love or physical attraction for him, nor is he the person she seeks to gold-dig from. Connie uses Flamarion so she can wed a bicyclist in the show Eddie (Stephen Barclay). As the femme fatales in noirs like to use and manipulate men to achieve selfish desires, Connie seduces Flamarion with more than just sex appeal. She plays into Flamarion's sentimental weaknesses by looking through his items to find out about his ex-wife, who has broken him. Mentioning her angers Flamarion, but Connie creates a false, helplessly innocent personality to give Flamarion hope for new true love and, in return, help her leave her abusive husband. By penetrating Flamarion's past and using a facade, he has contacted his sensitive side that he has hidden for so long and is on his knees to do anything she says. And like almost any seductive femme fatale, if it is not stealing or blackmail, it is murder she manipulates him to do. People like to remember criminals such as Vince Stone in The Big Heat, the Stranger in Stranger on the Third Floor, or Harry Lime in The Third Man as the typical main baddies in film noir. However, femme fatales often at times serve as the main villain as well. Notable examples include Vera in Detour, Kitty in Scarlet Street, and Ellen in (the debated color noir) Leave her to Heaven.

Fear in the Night reverses the typical film noir tropes in The Great Flamarion. The film has no femme fatale, or at the very least, one that does not meet any of the conventions. The female characters in the movie exist more as moral support or a victim than seductive villainesses or innocent heroines that attempt to take control of the situation (like Jane in Stranger on the Third Floor or Debby in The Big Heat). They are the Susan Vargas from Touch of Evil and Katie Bannion from The Big Heat of their time. The antagonist is not the typical criminal people would generally think of when contemplating film noir. The criminal, Mr. Belknap, is a hypnotist who rarely gets his hands dirty-not too different from the crime bosses or manipulative femme fatales who use their power or charms in order to persuade people to do their dirty work. In The Great Flamarion, the first time Flamarion starts developing some feelings for Connie is as he is doing routine target practice for his act. As Connie starts sweet-talking him, the reflective light from the pendulums Flamarion shoots move back and forth on the wall as the sound of ticking is played on the soundtrack. The image symbolizes Flamarion becoming hypnotized by Connie's beauty and claims about him. Fear in the Night uses hypnotism in a literal sense. No desires attract Vince, he is instead forced to do Belknap's bidding without free will.

Paul Schrader states "Film noir is not a genre, as Raymond Durgnat has helpfully pointed out over the objections of Higham and Greenberg’s Hollywood in the Forties. It is not defined, as are the western and gangster genres, by conventions of setting and conflict but rather by the more subtle qualities of tone and mood." Both films partially follow the conventions of the film noir style. Both films have a startling and puzzling beginning, but each has a different narrative. Flamarion and Vince are doomed protagonists, except one commit murder to achieve a desire while the other is in an uncontrollable trance, willing to admit a crime. And both films either do not share a femme fatale character or a vicious criminal. As different as the two films are in so many ways, the film noir style can still be felt and seen, not just in character and story, but also in terms of atmosphere. The grim abstract imagery visually presents the viewers with a constant sense of danger. A slow pace to build up a sense of urgency. Music that can be mournful, intense, or deceptive to emphasize the environment and characters. The clothing style subtly emphasizes the characters' personalities as the backgrounds do. These technical elements, familiar dramatic character tropes, and a suspenseful story relating to crime create film noir. It is difficult to pinpoint what film qualifies as film noir or not (noir infuses other genres, including westerns, heist films, and melodrama), as it has been debated for an extended period. However, there is something that can be felt within its tone and visuals that cannot be felt or found in classic crime films like The Public Enemy, Little Caesar, and The Petrified Forest. If there is one thing for sure about the appeal of film noir it is the ominous transgressive escapism. As Corey K. Creekmur nicely put it. "Loving film noir is thus somewhat analogous to the doomed hero of a classic film noir such as Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) directing his passion to the dangerous but exciting femme fatale and away from the safe but dull nice girl: our attraction and our reason, or our passion and our morality, are pulled in opposite directions. Whether we identify with the flawed hero or the femme fatale (there’s little desire to identify with the good girl), we want to be bad. The love of film noir is similarly transgressive, if only in fantasy."

Friday, February 16, 2024

Do the Right Thing: The Most Unconventional and Honest Film About Racism

Sal's refusal to put pictures of black people up is not the only indication of his racism. When describing to his son Pino why he does not move his business, he refers to the community as "these people," indicating he does not see them as equal despite not sounding mean. To Sal, friends are people who put money in his pocket, but he never considers the community as his friends. He claims Mookie is like a son to him though never treats him like his sons because of his race. The only scene when Sal is fatherly towards his staff is with Pino, who, out of his two legitimate sons, is the one who is openly racist. It is not until the end of the film when Sal's racism is as direct as Pino's when Buggin' Out, and Radio Raheem confront him again. Sal, having enough of the two resorts to calling them racial slurs, lashes out in violence, and when Radio Raheem dies in the chaos, he shows no remorse. Sal is not a non-racist man who said and did the wrong things irrationally in the heat of passion because the film indicates multiple times that he is racist, just not directly as shown in other films. And Lee's portrayal of Sal as an ordinary man makes his racism more real. As Hollywood would like to make racists clear-cut villains, they tend to overlook that racism is not just from the extremist but could be from your friendly neighbor, vendor, or relative you know.

Systemic racism is why Mookie throws a garbage can into his boss' window to start the destruction of Sal's Pizzeria. Sal's racist colors are fully revealed, and the police murder a defenseless man in front of the pizzeria. From seeing everybody go at each other in the neighborhood all day in the burning heat and seeing Sal and the police get away with their crimes while his friends take all the blame, Mookie has had enough of the injustices. Mookie does the right thing, and Sal's place is in ashes, which should end the film either with a celebration or with Sal reforming after seeing the error of his ways, but the film does not end happily. Mookie did the right thing at the expense of losing his job. Sal's business is destroyed, but he will receive insurance money to start over. The riot did not end racism in the neighborhood as long as systemic racism still exists to keep everyone divided.

Tuesday, January 16, 2024

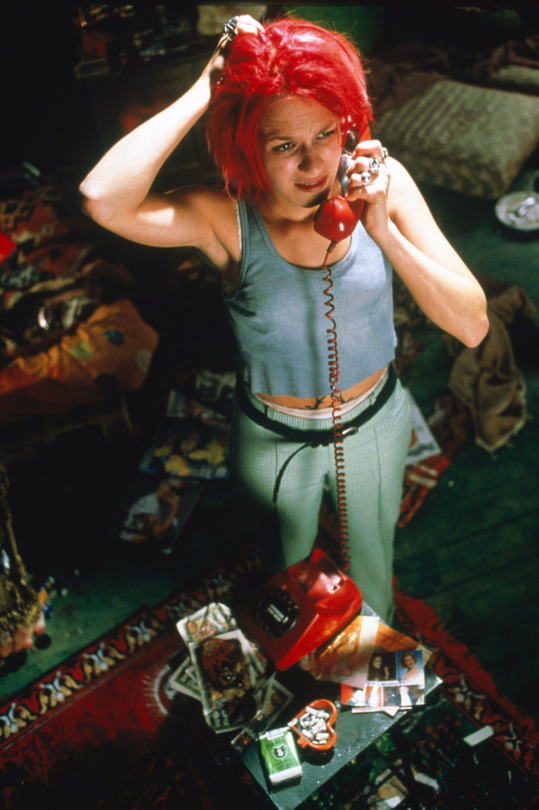

Run Lola Run

When American film scholars think of German films, a few of the following pop into their minds. There is German Expressionism from the silent era for having sets that appear nightmarish or otherworldly, as these films would handle dark themes like corruption, horror, and psychology. The Nazi propaganda films that looked stunning yet had dark purposes underneath their beautiful imagery that would further influence American propaganda films (the Why We Fight series directed by Frank Capra is a prime example). And the experimental and grittiness of Germany captured in New German Cinema by filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, and Wim Wenders. Each German cinema era has its unique, unforgettable style that has continued to influence other countries as time progressed. A particular film from the country released in 1998 that would carry on the country's innovative film techniques is the experimental thriller...

The first image takes place in a dark abyss with a cuckoo clock covered with gargoyles ticking as the pendulum swings, appearing like an opening to a horror movie. Shortly after, the camera enters inside the gargoyle's mouth, and it is daylight where the footage is now sped up as the camera rushes through a crowd of people, occasionally slowing down to give focus to some of the people. Throughout this sequence, a narrator's voice questions our place in the game of life. The last person the camera focuses on during the sequence is an authority figure breaking the fourth wall by addressing the audience with the rules of a ball game, takes out a ball, and an aerial shot shows him kicking the ball up to the sky where the crowd below form the letters for the film's title. From the beginning, the film makes itself clear that it is visually and tonally not going to be a conventional action thriller. The film is instead going to go crazy with its surreal direction expecting the audience to have fun with it, as opposed to creating a gritty, realistic action suspense film that is supposed to keep audiences fearfully on the edge of their seat.

That is not to say the film is not based on thrills either. The film's premise revolves around the title character Lola (Franka Potente), the girlfriend of the criminal bagman Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu). After losing a bag full of 100,000 Deutschmarks, he desperately calls Lola for help, informing her his boss will kill him if he does not receive the money. The only solution Manni can think of to get back the money is to rob a nearby supermarket. Lola tells Manni to wait for her, but Manni only gives her 20 minutes to produce the money before he resorts to robbery. It is up to Lola to race to the rescue of her boyfriend while figuring out how to replace the money Manni lost. A story as intense as this with a limited runtime regarding the stakes would easily fill a film's third act, making for a riveting climax. However, this is how the film's plot begins after the prologue, without any apparent warning, placing the audience in Lola's position. Except for getting visual exposition, the action immediately kicks off.

Little is described about Lola and Manni's characters to get the audience emotionally invested in their personalities. One would think as Lola runs to save her lover; the film would take a break from the action a few times to show flashbacks of Lola's past with Manni to build an emotional interest in them. But aside from the flashback in the opening scene and two flashbacks of them in bed together asking each other about their feelings, the film does not dwell long in the past for audiences to connect to the characters. The emotional intrigue for the characters and what we learn about them is focused on the present and probable future. Through each encounter, something is learned about the characters, especially Lola, whether it is a dramatic scene of Lola talking to her father, encountering a pedestrian, or her eagerness to help her boyfriend as she runs. Given the film's intense premise and bizarre direction, the audience's attachment and understanding of the characters are mainly described through actions rather than dialogue.

Just like the prologue, the film does not at all hold back from exploiting various film styles and techniques. Some scenes are shot with a 35 mm camera to make Lola's journey appear big and intense. In contrast, some scenes are shot with a video camera to create a documentary feel for certain scenes, like when a homeless man finds the bag of money as if we are watching footage from a security camera. The film is primarily shot in color, with the colors red and yellow popping out, connecting to the film's primary leads (such as Lola's hair and the various locations where Manni waits). But the film has certain scenes shot in black and white, used explicitly for the flashback sequence regarding Manni's mistake to present old grainy memories of the past, like watching an old film. The film even briefly tells its narrative in other forms of media. When Lola runs down a spiral stairwell in her apartment, avoiding a tenant's dog, the scene is depicted in hand-drawn animation. Another instance involves photographic montage. These montages usually happen for a few people Lola briefly encounters, showing their future.

The film's decision to constantly change its style may come across as obnoxiously pretentious, but it is the exact opposite. As random as the techniques are, it does not distract from the overall focus nor change the film's tone. And by the time the film reaches its second act, the experimental nature of the film starts to feel more like the film's norm. In many ways, the film's style is reminiscent of the American film Natural Born Killers (1994) by telling a crime drama with dark humor as the style keeps changing. Natural Born Killers experimental nature was to criticize how the media glorifies crime stories; in this film's case, it represents trial and error when dealing with the unpredictable in the game of life.

If Natural Born Killers is supposed to resemble a product of the problematic media the film attacks, Run Lola Run resembles a video game for its commentary on life. Lola's dyed red hair and wardrobe resembles a video game avatar like Lara Croft from Tomb Raider if she were designed as a fighter for a Japanese style fighting game. The actions of watching Lola run as she dodges one obstacle after another, stopping to gain help, and make it to her destination before time runs out plays out similar to the style and objectives in games like Super Mario Bros. or Crash Bandicoot. The soundtrack itself is an energetic electronic score sounding urgent yet excitingly playful at the same time, that would not sound out of place in games like Sonic the Hedgehog, or Tekken. Without giving too much away to further on the film's attempt to resemble a video game, for every time Lola fails, the way Lola finds another way is similar to how gamers figure out how to finish objective in a level they struggle finishing.

The film is not only a filmmaking spectacle, but is highly entertaining, well-acted, fast- paced, action-packed, has intriguing characters, and a unique way of visual storytelling. The film’s plot has a clear end goal, with characters who are easily identifiable, but leaves more than plenty of room open for interpretation and theories with small blink and miss details in every frame. It may also be one of the best video game movies in existence without serving as a film adaptation of one. Run Lola Run is not the first of its kind in German film to use a range of styles and film techniques to have a deeper meaning under a simple story, but it is regardless one of the best films of that type, making it one of the most ambitiously innovative films from the country.