For this Halloween, I would like to look into a milestone slasher film...

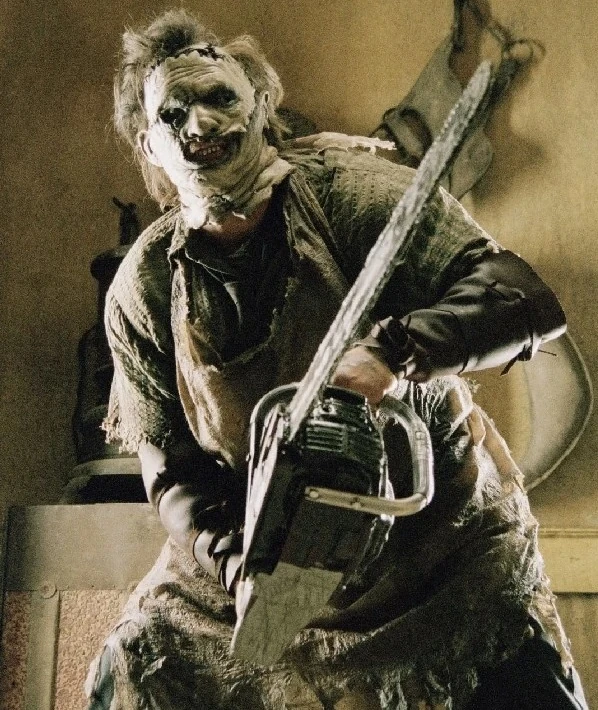

Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) is not only one of my favorite slasher films of all time and one of my all-time favorite horror films in general, but it is one of the few horror films that manages to frighten me. As a huge horror fanatic who loves watching dark, scary, grotesque, and monstrous imagery, I hardly ever get scared by horror films. I can see how the film achieves its scares effectively; but I am more impressed with how it is executed rather than finding myself frightened or repulsed. As a kid in Middle School, I heard about the film's fearsome reputation from critics, horror enthusiasts, and family and friends, as well as the appeal of the villain Leatherface in pop culture among slasher villains like Jason and Freddy (who I was first introduced to in a Roger Corman parody horror film Transylvania Twist (1989)). All this information and praise made me curious to see how the film lived up to its popularity.

At the time, my dad purchased a copy of the movie as a Christmas present but mistakenly gave me its 2003 remake. Like other horror films I saw then, I was excitedly entertained by the film's villains, atmosphere, and excessive use of gore instead of being scared. Honestly, in retrospect, I do not think the remake is as bad as critics made it out to be. It is not as good as the original, but it is creative with the kills; Leatherface is highly more intimidating than he was in any of the sequels, and is supported by a strong cast, especially R Lee Ermey as a crazed killer sheriff whose performance alone is enough to make the film worth seeing. When I finally saw the original nineteen seventy-four classic in my mid-twenties, I was so creeped out, shocked, disgusted, and uncomfortable watching it (as the film intended); by the time, the movie was over, I felt relieved to escape the madness as if I were suffering with the film's protagonist. And the crazy part is the film has less blood than the remake had. During a recent rewatch with the film still having the same effect, I wanted to dig deep into how the film achieves its scares and how it came to be.

From the silent era to the late nineteen-forties, horror films mainly focused on the supernatural, like vampires or werewolves, or stories of mad scientists that were typically period pieces or existed in a fantasy world in faraway lands. The scares in the movies relied on monster make-up, a quiet foreboding atmosphere often resembling nightmares, the monster and the characters' psychology, and (for the time) shocking scenes of people getting killed, often by strangulation or happening off-screen with the aftermath shown. By the fifties, known as the Atomic Age for horror films, audiences were less interested in horror stories taking place in the past and more so in Sci-Fi horror due to the tensions of the Cold War with the fear of the widespread of communism and the destruction from the atom bomb. Sci-fi films about alien invasions and giant monsters destroying the city would be an allegory for people's fears at the time.

As people went to the theaters to watch death and destruction caused by Sci-Fi creatures, a sick maniac would casually walk among the streets of Plainfield, Wisconsin, known as Ed Gein. Gein grew up in a strict Christian household with his alcoholic father, older brother, and domineering mother. Gein's mother read from bible testaments while preaching hatred, especially towards women, viewing them as disgusting and unholy creatures. Despite the abuse Gein's mom would bestow upon him, he would never stop trying to please her with all his best efforts, even if it were never good enough for her. After his mom's passing, Gein, alone and lost without her, would seal off her room and keep the house the same when she was alive and talk to her. Unsatisfied with his actions to keep his mom's spirit alive, Gein would go to the cemetery, digging up graves of middle-aged women and bringing them home. Gein would use the bodies he snatched by using their bones to make furniture and trinkets, make clothes and masks out of their skin (one designed to resemble a woman so he could become his mom), and eat their organs. Gein's madness drove him to murder two women, a bartender named Mary Hogan and hardware store owner Bernice Worden. In 1958 shortly after the murder of Worden Gein was arrested.

Gein was not silent about his crimes or reasons after he was caught, making him a top headliner at the time. His story inspired author Robert Bloch to write a novel about a killer obsessed with his deceased mother called Psycho, which would later be adapted into a film famously directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Amusingly Hitchcock had a gimmick where he would have theaters not let people in if they came late to the show so that people would not question what happened to the film's main character and marketable star, Janet Leigh. Although Hitchcock's no stranger to creating breathtaking suspense and stellar camerawork, the film's controversy with the censors, the infamous shower scene, the ear-screeching score, and the twist ending made it one of the most popular films of its time. Regarding slasher films, Psycho is not the first, nor the only, slasher film to come out that year as Peeping Tom (1960) came out a few months prior in the U.K. before receiving a release in the U.S. in 1962. But the film was still a popular game changer.

Though sixties horror would continue to produce psychological thrillers and supernatural horror films, George A Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968), would have as big of an impact on the genre and filmmaking as Psycho did. Romero's zombie horror classic was an independent production shot on a low budget with a cast of unknown actors. While critics did not heavily praise the film as it is now, it was popular at Grindhouse theaters and Drive-Ins. Audiences found the film frightening for its unique portrayal of zombies, use of gore, and unhappy ending. But the most significant fears came from the fact that the film was not set in a past or fictional environment, but the zombies were attacking people in a typical American household, making the threat feel close to home, just like in Psycho. Although Romero reportedly had no political underlining when creating the film, with the news media's focus on the violence during the Civil Rights Protests and the war in Vietnam, people could not help but see a parallel to the real-life horrors they were witnessing at the time, whether it was zombie's causing unwanted destruction to property, or heavily armed soldier-like men mistaking civilians for zombies.

1969 to 1970 marked the transition of the loss of optimism held by the flower power youth in the sixties. The infamous Hippie cult, the Manson family, led by Charles Manson, committed a series of murders. The Altamont Free Concert, which was supposed to recapture the positive mark Woodstock left, became a place of death and rioting. Young protesters were killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University. And the war in Vietnam was only getting worse as the days went by. Night of the Living Dead's low-budget and unconventional creativity with horror that gained screams and popularity while showing a dysfunctional America inspired other independent filmmakers to make exploitation horror films showing the faults of the American dream. The monsters in these films were less about zombies and creatures and more about vicious criminals who would hunt or trap their prey in a secluded location.

One of the famous films of that kind in the early seventies was The Last House on the Left (1972), which helped boost the careers of the film's director Wes Craven and producer, Sean. S. Cunningham. Like Night of the Living Dead, the film did not receive a strong reception from critics (except from Roger Ebert). Still, Grindhouse theater audiences were horrified by the film's documentary-like presentation of watching two young women from the hippie generation getting brutally raped and killed by vicious criminals in the woods. And underneath its tasteless violence was showing audiences the literal death of the hippie generation while satirically poking fun at the unreliable role of police authority, where it is up to the civilians to fend for themselves against the killers in their own home.

Independent filmmaker of the time, Tobe Hooper from Austin, Texas, was hardly receiving attention with his experimental film Eggshells (1969) and TV documentary Peter, Paul, and Mary: The Song is Love (1971). Noticing the popularity of horror exploitation films at the time, Hooper wanted to make a marketable product reflecting the popularity of the time. Hooper was already a fan of horror, particularly horror films made by the British film production company Hammer, which specialized in doing remakes of classic horror films like Dracula and Frankenstein in the late fifties with color, sex appeal, and lots of blood, spawning numerous sequels that would lead to the mid-seventies. Hooper would also hear the stories about Ed Gein from his Wisconsin relatives when he was younger, which stayed with him. Hooper even feared leaving the city limits of his own home due to the unknown dangers in the desert. His passion, fears, and the popularity of independent horror films at the time became his source of inspiration and drive to create the classic horror film The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

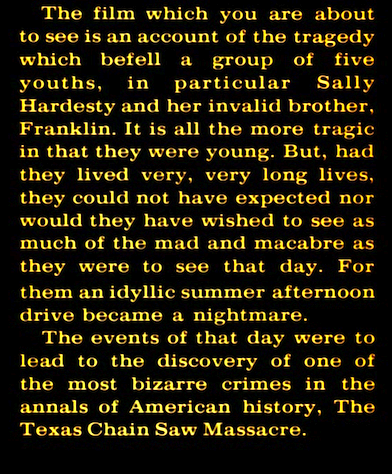

The posters for the film would promote it as a feature based on actual events by claiming, "What Happened is true. Now the motion picture, that's just as real." and that the film captures "America's most bizarre and brutal crimes!" The film also contains a prologue with an opening scroll and a narrator telling the audience the film "is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths," like The Last House on the Left's prologue. Of course, this is far from the truth, aside from the killers being loose based on Ed Gein. Regardless of the film's fiction, the film overall carries a grainy raw look with occasional scenes and moments that appear like a documentary (like the photos of corpses taken at the beginning, or a victim finding a living room with furniture made from dead body parts), to make it seem like the events happening were real. The film hardly ever feels like it is playing on traditional horror gimmicks to win audiences over, therefore coming across as a picture with a horrific cautionary tale to tell.

One of the grounded elements is the depiction of the teenage victims. Usually, in horror films, they are too over the top through their acting, typically playing one-dimensional stereotypical role, while exploiting their looks for sex appeal before their death. With the cast in this film, the characters feel less like stereotypes and more like regular down-to-earth teens. The only character who comes close to the cartoony teenage stereotypes is Franklin (Paul A. Partain) due to his weird personality and moments of comedy. But at the same time, he never goes too over the top to the point where he feels like a forced comic relief. I cannot say the teenagers as characters, they are intriguing but are at the very least believable and relatable to feel for their torment. And while nudity and sex are always welcomed in a horror film of its nature, it is surprising that the film does not resort to it, knowing a pointless sex scene would be unsubtly winking to audience members who want to be aroused.

The exclusion of sex is as shocking as the film's lack of gore. With a title as gruesome sounding as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the film is not showered with as much gore as one would think. The film only uses it when needed, like when someone gets cut, the blood during a chainsaw kill splattering on Leatherface, or when the final victim is covered in blood. One would think that scenes like this would be enough, but the shots usually do not linger too long on the bloody wounds nor show a ton of blood spilling. When I think back to the film, I think less about chainsaw murders and more about murders with the sledgehammer. Sure, Leatherface runs around with the chainsaw, but there is only one murder involving the film's title weapon. There is one scene where Leatherface is slicing up a dead body, but nothing is shown, no blood or shots showing the chainsaw penetrating through the body.

The film shows enough graphic imagery, but its terrors leave more to the imagination rather than showing the gruesome detail of the kills. For instance, a character is taken away and placed on a large, rusty meat hook. A shot of her skin is about to make contact with the hook until the scene cuts to a low-angle medium shot of her hanging with a dead body on a table before her. Despite not seeing her bleed, the screams of pain and the sound of the chainsaw cutting up her boyfriend's dead body sound brutal, and her reactions and movements indicate the sight she is seeing, and the pain she is feeling is worse than it looks. Another example is the death of the first victim. The kill is shot from a long distance and happens for only a few seconds, but the surprise of Leatherface and the grotesque sound of the hammer pounding the man's skull is more sickening than seeing it up close or seeing blood spill all over the place. Blood is shown on the dead body, but it is not so much the blood that is scary, but how the body is involuntarily shaking and banging hard on the floor, with the scene ending with Leatherface bringing the body into his kitchen and violently shutting a slide steel door loudly. The film shows very little but enough to make audiences disgusted, strongly backed up by its realistic atmosphere, little details, and sound design.

Another contribution to the film's success with terror is how the tension is built, backed by the slow pacing and the actors portraying the cannibalistic family. With the film's opening scroll and nauseating imagery of dead bodies shown in the film's first few scenes to set up the film's documentary-like style, the scene when the teenagers pick up a hitchhiker (Ed Neal) is the first scene to show the film's skills when creating tension perfectly. When looking at the hitchhiker's odd behaviors, large beauty mark that looks like dried blood and hearing him expressing joy in killing animals in the slaughterhouse, there is instantly a feeling of unease. Obviously, this guy is going to harm one of the teens in the group, but it is never certain when he will since his actions are always unpredictable. One moment he has a picture of dead animals from the slaughterhouse, then he looks at Franklin's knife and cuts himself with it. He does not use the knife on Franklin but returns it to him and shows the blade he carries, which is a straight- edge razor. Yet, he does not use it and puts it back. No score is played during the encounter with the hitchhiker to build tension; instead, the sound of country music on the radio makes the meeting more uncomfortable for the how its pleasant, upbeat music contrasts with a happily crazed man who feels dangerous. And the tightly confined space of the van with no place to run, with characters who are uncomfortable yet too fascinated by this man's mysterious nature to kick him out, places the viewer in the same position. By the time this man does strike, the attention is on him burning a photo he took of them with his camera, creating a sense of absence for him to assault them at the moment since this man does one crazy thing at a time, making the sudden attack effective. But for me, the scariest moment in the sequence is how he smears the blood on his hand on the van to mark them after getting kicked out. The teenagers have driven away from him, but the blood-stained markings on the van keep a sense of unease with the feeling that this will not be the last we see of him.

The film's most traumatic scene does not involve any killing; it is when Sally is dragged to join the family of killers for dinner. Throughout the scene, the viewer feels as trapped as Sally is. The scene uses various shots, including titled angles, overhead shots, close-ups, and long shots, creating a disjointed feel matching the insane performances of the actors. The sadistic family yelling and arguing and the screams from Sally barely have a moment of silence, as the close-ups of the characters' threats or suffering feel excreting close, increasing the anxiety present. Like the hitchhiker's in the introduction, the suspense and terror come from the unpredictability of the actions. We see the family constantly abuse, harass, and poke Sally like they would treat an animal from the slaughterhouse, increasing the tension and repulsion. Still, these characters reveal something stranger about themselves. Apparently, this family has a grandpa who was mistaken for a random corpse in an earlier scene. It would be creepy enough for the family to bring a corpse to the dinner table, but expected since the house and dining are decorated with dead bodies and even have an old dead corpse in one of the rooms. But it turns out the grandpa is not dead despite his corpse-like appearance, but is barely alive to speak and move, which has brought him back to infancy. He does not even have the strength to eat tender meat; he has to suckle on the blood from Sally's freshly cut finger like a baby breastfeeding from their mother's milk. Leatherface also changes his wardrobe and face masks in the scene more than once. Before the scene, Leatherface wears a male facemask and a meat apron. In the dinner scene, he wears an old lady's face while dressed in feminine clothing when preparing the meal, and at the dinner table, he wears a younger lady's face with terrible make-up and a traditional southern dinner jacket. In concept, this scene should be funny for how bizarre these characters are, and Tobe Hooper intended to give the film some dark comedy, which he would exploit in the sequel. However, the unpredictability of the family's actions, the dirty and gritty atmosphere, camera work, strong acting, and slow pacing make the scene one of the scariest scenes ever shown on film.

A secret ingredient to the feeling of pain, suffering, and discomfort in the film was that the actors were suffering. Given the film's low-budget production, despite Hooper's best efforts to keep his actors safe and healthy, many things went wrong during the shooting. Some of the blood shown on Marilyn Burns was from actual injuries she had during the production; this was due to her accidentally cutting herself on the branches when running. Even after using a stunt double to jump out the window, Burns injured herself when shooting the insert shot of falling on the ground. The dirty cloth placed in her mouth to gag her in the dinner scene was an actual dirty cloth found on the floor. When watching the film, the brutal heat and humidity of the summer are felt, and in reality, that becomes a significant problem in filming. Hooper used real bones from dead animals he received from a veterinary to decorate Leatherface's house. Unfortunately, since there was no air conditioning, and the windows had to be closed and blocked to create the illusion of nighttime, the heat combined with the studio lights would rise to over one hundred twenty degrees Fahrenheit, making the bones and food smell so bad that it caused the actors to vomit continuously. The heat and sickness from the smell were so foul that Ed Neal thought making the film was much worse than his service in Vietnam. And this is only to name a few of the actual horrors when making the film. No film should ever be worth getting hurt over, but the fact that the cast and crew fought through it for a movie that they were expecting not to be the classic it became, while insane, is something to commend and a feeling that does come through in the final film.

Though modern audiences may find the film tamed and even silly, the film nonetheless was not only one of the most disturbing pieces of film for its time, but still holds up as a frightening movie. If a person goes into the film expecting buckets of gore, the person is better off watching the remake. But in terms of realism, giving more by showing less, building suspense, and having surprises at every turn, this film exceeds. And overtime filmmakers like Sam Raimi, Brian De Palma, and Quentin Taratino (to name a few) would incorporate ideas and elements from the movie in their work. The film was a pain to make, but in the end, it became one of the most popular horror exploitation films of all time proving a masterpiece can be made with so little, just like the film’s predecessors Night of the Living Dead, and The Last House on the Left.